Nehru and Jinnah had the same problem. Their daughters loved men they did not approve of. Children of ambitious fathers, Indira and Dina, both, carried their fathers’ hopes and lived with their mothers’ pain. They were daughters who were raised in the mould of the young English ladies their fathers had gone to school with. Jinnah’s daughter, Dina was born in Britain and, like Indira, went to school there.

What the girls did not know was that it was all fine and dandy to wear modern ideas but you don’t go to bed in them. Both girls crossed the line and fell in love with men of another faith.

Dina was born on the night between August 14 and 15, 1919. She made a dramatic entry into the world, announcing her arrival when her parents were enjoying a movie at a local theatre in London.

Stanley Wolpert’s Jinnah of Pakistan records:

“Oddly enough, precisely 28 years to the day and hour before the birth of Jinnah’s other offspring, Pakistan.”

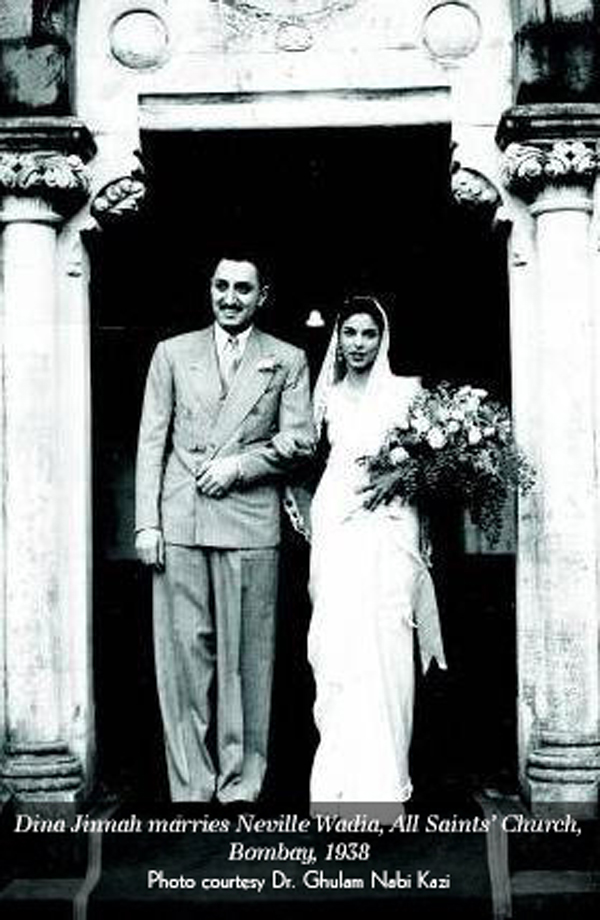

When Dina was introduced to Neville Wadia, she was 17-years-old. The year was 1936.

Neville was born to a Parsi (Zoroastrian) father and a Christian mother. His father, Sir Ness Wadia, was a well-known textile industrialist in India. Neville was born in Liverpool, England, and educated at Malvern College and Trinity College, Cambridge.

Mahommedali Currim Chagla, who was Jinnah’s assistant at the time, writes in his autobiography Roses in December:

“Jinnah asked Dina ‘there are millions of Muslim boys in India, is he the only one you were waiting for?’ and Dina replied, ‘there were millions of Muslim girls in India, why did you marry my mother then?’”

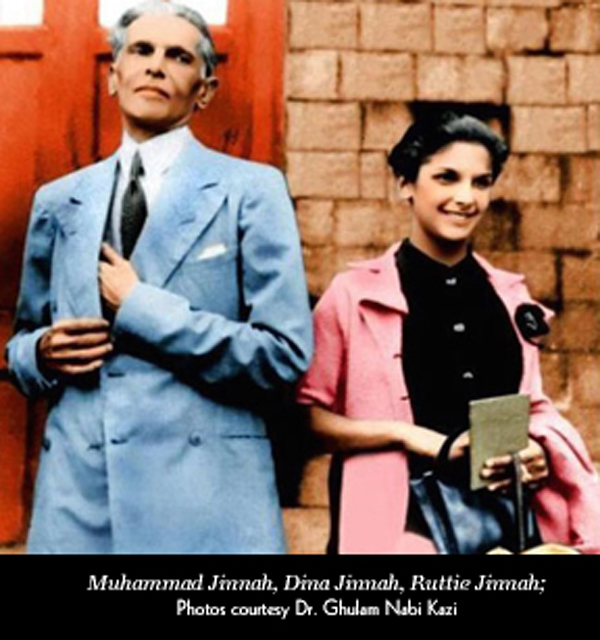

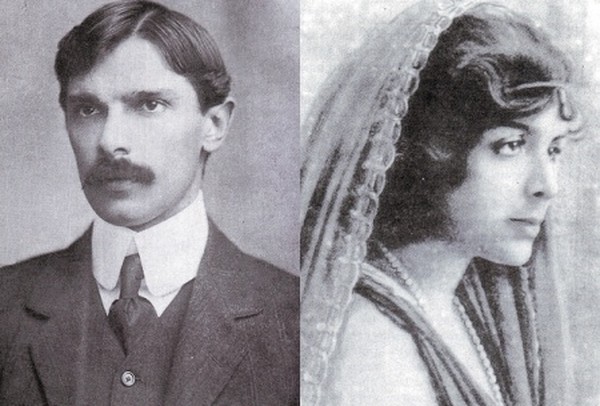

Jinnah and Ruttie:

Jinnah, you see, was no stranger to love. We learn about Ruttie and Jinnah from Khwaja Razi Haider’s book Ruttie Jinnah: The Story Told And Untold.

Twenty years after the death of his first wife, Jinnah had turned to mush in the arms of 16-year-old Ruttie, Dina’s mother-to-be, and a Zoroastrian to boot. They wanted a civil marriage and the law at the time stated that you had to forswear religion to get married in court. Haider explains that this meant Jinnah had to resign his Muslim seat in the Imperial Legislative Council. Ruttie solved the problem by embracing Islam and marrying Jinnah. Love that had blossomed while horse-riding in Darjeeling was sealed with a forbidden kiss.

PHOTO: COURTESY DR. G.N.KAZI

Ruttie’s father, Sir Dinshaw Petit, a textile magnate and Jinnah’s client was horrified that his only child was marrying Jinnah, a man of another faith, and had forbidden them from meeting each other. Sir Dinshaw went to court and got a restraining order. The couple had to wait for two years before Ruttie reached legal age and was able to marry Jinnah and leave her parental home.

It was love’s early days. According to Haider, when Jinnah, or J as she called him, worked in stuffy offices, with stuffy men, discussing stuffy things, while Ruttie, the flower of Bombay, waited patiently in the musty rooms of courts of law. She travelled with Jinnah to meetings, including the Congress session in Nagpur, and spoke vociferously in favour of Hindu-Muslim unity in the face of the colonial enemy Britain.

PHOTO: COURTESY DR. G.N.KAZI

Jinnah admired and indulged Ruttie. Haider shares an interesting anecdote of their dinner at the Government House. The story goes:

Mrs Jinnah wore a low-cut dress. While they were seated at the dining table, Lady Willingdon, Marie Freeman-Thomas, Marchioness of Willingdon asked an aide-de-camp (ADC) to bring a wrap for Mrs Jinnah, in case she felt cold. Jinnah rose from the table, and declared,

“When Mrs Jinnah feels cold, she will say so, and ask for a wrap herself.”

Then he led his wife from the dining-room, and from that time on refused to go to the Government House again.

A precarious balance:

However, real life has a way of sneaking up. The first few years of Jinnah’s marriage to Ruttie also coincided with challenging times at work. Gandhi returned to India and his political tactics were different from those of Jinnah’s constitutional ones.

During the second and third year of his marriage, Jinnah was forced to make three remarkable decisions that reduced his role in India’s freedom struggle: he resigned from the Imperial Legislative Council, the Home Rule League and Indian National Congress. The graph of Jinnah’s career showed an increasingly downward trend. During the 1920 session of Congress, with Ruttie by his side, Jinnah saw Gandhi hijack the movement. As opposed to Jinnah’s constitutional ways, says Jaswant Singh in his book India, Pakistan Independence, Gandhi was taking the movement to the streets with chaotic demands like Purna Swaraj (complete self-rule).

“Your way is the wrong way: my way is the right way—the constitutional way is the right way,” Jinnah had said to Gandhi.

Jinnah parted ways with the Congress. He held no public office except for his membership of the Muslim League. Moved from the national stage, Jinnah now had a smaller platform to stand on.

Dina was a year old when India veered in the direction of non-cooperation and civil disobedience, and her father, Jinnah, disagreeing with Gandhi’s tactics, took a back seat. The family immersed themselves in the Parsi community. Professor Akbar S Ahmed in his book Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity, records how the family travelled through Europe and dined with friends at Savoy and Berkeley during that time.

Gandhi was jailed in March, 1922. Ruttie and Dina saw Jinnah throw himself into the 1923 November Central Legislative Assembly elections to their neglect. Jinnah fought for adequate representation of the Muslim legislative assemblies even as Gandhi was released from jail.

Haider details how, at home, Ruttie, and nine-year-old Dina took a back seat in Jinnah’s life and for Ruttie, the psychological stress caused colitis to flare up. They moved out of the house in 1928 to the Taj Mahal Hotel. Jinnah accepted his role in the failing marriage,

“It is my fault: we both need some sort of understanding we cannot give.” [Haider]

“Mrs Jinnah had already sailed for Europe, with her parents, when her husband left Bombay in April 1928; his political career in dark confusion, and his one experiment in private happiness apparently wrecked for ever,” writes Hector Bolitho in the official biography called Jinnah.It is from Bolitho we learn that Diwan Chaman Lall, a colleague and friend, took a voyage to England and after the voyage declared, “he is the loneliest man”.

Soon after the ship arrived in England, Jinnah went to Ireland, and Diwan Chaman Lall to Paris where Ruttie and Dina were staying. Chaman Lall had been in his hotel only a few minutes when he learned that Ruttie was in a hospital, dangerously ill.

He described the story to Bolitho,

“I went to the hospital immediately. I had always admired Ruttie Jinnah so much: there is not a woman in the world today to hold a candle to her for beauty and charm. She was a lovely, spoiled child, and Jinnah was inherently incapable of understanding her. She was lying in bed, with a temperature of 106 degrees. She could barely move, but she held a book in her hand and she gave it to me. ‘Read it to me, Cham,’ she said. It was a volume of Oscar Wilde’s poems.

“A few days later Jinnah arrived from Ireland. I waited in the hospital while he went in to see her—two and half hours he was with her. When he came out of her bedroom, he said ‘I think we can save her … I am sure she will pull through’. Ruttie Jinnah recovered and I left Paris, soon afterwards, for Canada, believing they were reconciled. Some weeks passed, and I was in Paris again. I spent a day with Jinnah, wondering why he was alone. In the evening, I said to him, ‘Where is Ruttie?’ He answered ‘we quarrelled: she has gone back to Bombay’. He said it with such finality that I dare not ask any more.”

Jinnah found it difficult to maintain his position at the national level given Gandhi’s arrival and rapid ascendancy. In 1928, Motilal Nehru presented the Nehru Report in Calcutta and came out squarely on the side of Gandhi. Jinnah sensed an unmatchable opponent. He spoke about the danger of ignoring the insecurities of the minorities. As he left, he said to Jamshed Nusserwanjee,

“Jamshed, this is the parting of the ways.” [Jaswant Singh]

“Dina, however, maintained that Ruttie died of colitis or something more complicated, but it certainly was a digestive disorder. The disease caused Ruttie excruciating pain towards the end. At one stage, an overdose almost killed her, and even suggested to some people that she had attempted suicide,” wrote Akbar Ahmed in his book Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity.

While Jinnah was preoccupied with work troubles, Ruttie lay in the Taj Mahal Hotel with a broken heart. Dina watched her mother’s life ebb away. Two months later she died—not yet 29-years-old.

Jinnah sat in the burial ceremony with Kanji Dwarkadas beside him. He talked of his political worries even as her body was lowered into the ground. He broke out his reverie when asked to throw a handful of earth. The finality of it hit him. As the idea of a new country birthed in his frustrated mind, his love left him to inhabit another world. He had been check-mated both by his political rivals and his lover. Ten-year-old Dina watched her father crumble to the ground as he wept uncontrollably.

“Ruttie’s death devastated Jinnah, according to Dina… A curtain fell over him, said Dina,” writes Akbar Ahmed.

Motherless Dina left for England with her father who had decided to abandon politics and settle in London along with his sister, Fatima.

“I felt so utterly helpless,” said Jinnah, to the students of Aligarh eight years later, about his exit of 1931, recounts Akbar Ahmed.

Grey Wolf:

They moved into West Heath House in Hampstead; a three story villa built in the style of the 1880s with a tall tower which gave a splendid view over the surrounding country. Stanley Wolpert in To Charisma and Commitment in South Asian History writes about Dina and Jinnah’s time in London.

“Dina would have morning tea with her father, sitting at the edge of his bed. Breakfast was at nine o’clock, sharp. Bradbury, the chauffer took Jinnah to his chambers in King’s Bench Walk thereafter. On Saturdays and Sundays, they walked on the Heath to Kenwood past Jack Straw’s Castle, the inn where Karl Marx had sat drinking root beer with his daughter.”

PHOTO: COURTESY DR. G.N.KAZI

One day, home for the holidays from her English school, Dina came down for breakfast to find her father engrossed in a book by HC Armstrong on Kemal Ataturk called Grey Wolf, Mustafa Kemal: An Intimate Study of a Dictator. As 13-year-old Dina reached for the toast, Jinnah handed her the book,

“Read this, my dear,” he said, “It’s good.”

For days on, he talked about Kemal Ataturk. So impressed was he by him that Dina named him Grey Wolf.

Like any teenager, she loved to tease her father. She lightened his dark days. Dina did not realise her idyllic time with her father was coming to an end as the grey wolf was rising within him, calling him back to birth another child.

“Away with dreams and shadows! They have cost us dear in the past,” Mustafa Kemal seemed to whisper in Jinnah’s ear.

In 1933, Jinnah returned to India. The Hampstead home, where the Grey Wolf had lived, was sold. Dina went to live with her mother’s relatives in Bombay. [Wolpert]

The Muslim identity:

Young Muslim graduates thronged to Jinnah as their leader. Rising on the wave of their adoration, Jinnah finally saw the world he had wanted all along and he was not willing to risk it for any ideals. Gone was the man who had stood up for his wife’s low cut blouse. In his place was a man who Akbar Ahmed wrote in his book Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity, when visiting Balochi tribes, agreed with his host that it would not be wise for his sister, Fatima, who did not wear a pardah (veil), to go before the more traditional Balochi tribesmen. He scolded his hostess when she protested.

“You are trying to ruin four years of building up sympathy for the Muslim League among the tribesmen,” he said.

Later in his Presidential address, Jinnah would say,

“Women can do a great deal within their home, even under pardah.”

As Jinnah basked in the adoration of the Muslim masses and nurtured the idea of birthing a country, 19-year-old Dina spent more and more time with her mother’s family and the Parsi community. She turned to someone who was older than her and carried her mother’s spirit. She had found, it seemed, a combination of her parents, a lively Parsi gentleman, eight years her senior who had grown up, like her, in England—Neville Wadia.

Ruttie had been the only daughter of a textile magnate. And fatefully, Dina who had been 14 years of age when her mother died, married Neville Wadia, a textile magnate, within five years of her mother’s death. Neville Wadia would one day succeed his father as chairman of one of India’s successful textile concerns, Bombay Dyeing.

Marriage and estrangement:

Jinnah was livid that his daughter had not chosen a Muslim husband. Dina married Neville in 1938 against her father’s wishes, writes Chagla. In 1939, Jinnah pulled down the house of memories in Mount Pleasant Road and built a mansion. Jinnah asked for “a big reception room, a big veranda, and big lawns for garden parties,” recalled the architect Claude Batley as related by Akbar Ahmed.

The new mansion with its wide balconies, broad high rooms, and marble portico leading to the marble terrace was fit for the great leader that he was working to become. On his 64th birthday, Jinnah moved in. This house, a perfect backdrop for the future Quaid-e-Azam (the great leader) was not frequented by Dina. According to Chagla, Jinnah had disowned his daughter.

Dina and Neville had two children, a daughter and then a son. But Dina, like her mother, Ruttie, proved to be unlucky in love. Within five years of her marriage, she left Neville. They got separated in 1943, though the divorce never took place.

On July 20, 1943, an assassin entered the house with a knife to kill Jinnah, but was overpowered. Contrary to what Chagla wrote, Dina telephoned and then rushed to the house to see her father, writes Akbar Ahmed in Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity. In 1943, Jinnah became seriously ill and had to take a vacation in Srinagar to recover from an ailment in his lungs. As time passed, Jinnah’s temper got shorter and his aloofness grew. He focused single-mindedly on the negotiations with the Congress and the British to ensure the creation of Pakistan.

“There is the petulance that goes with such illness as Jinnah was suffering from,” said his doctor Dr Patel. [Ahmed]

Papa darling:

Jinnah succeeded in his fight for a separate homeland for the Muslims of India. Akbar Ahmed reveals that on hearing the news about Pakistan on April 28, 1947, even though she herself had no intention of moving to the new country, Dina wrote to her father.

“My darling Papa,

First of all I must congratulate you – we have got Pakistan, that is to say the principal has been accepted. I am so proud and happy for you – how hard you have worked for it.

I do hope you are keeping well –I get lots of news of you from the newspapers. The children are just recovering from whooping cough, it will take another month yet.”

She ended the letter with,

“Take care of yourself Papa darling. Lots of love and kisses”

She wrote to him again in June 1947 from Juhu:

“Papa darling,

At this minute you must be with the Viceroy. I must say that it is wonderful what you have achieved in these last few years and I feel so proud and happy for you. You have been the only man in India of late who has been a realist and an honest and brilliant tactician – this letter is beginning to sound like a fan mail, isn’t it?”

She ended again with,

“Take care of yourself. Lots of love and kisses and a big hug.”

Jinnah was 70-years-old when he boarded the plane on August 7, 1947 and flew to Karachi forever as the Governor General and Baba-e-Qaum of his new born child, Pakistan.

As he stepped onto the aircraft, Quaid-e-Azam looked back towards the city in which he was leaving behind forever his beloved Ruttie, whose grave he had visited the previous evening; their daughter Dina; a grand-daughter, a four-year-old grandson, Nusli holding on to his grandfather’s hat; and a house on the hill. [Haider]

He said,

“I suppose this is the last time I’ll be looking at Delhi.” [Akbar Ahmed]

He bid a final goodbye with a smile on his face. She would not go to her father’s new home with him and he would die in a year’s time. His lungs, riddled with tuberculosis, finally caught up with him.

Jinnah visited Ruttie’s grave a day before he left India forever. Dina did not travel to Pakistan until her father’s funeral in Karachi in September 1948. Their relationship would become a matter of legal conjecture and hair splitting. [Wiki]

Dina’s son, Nusli Wadia, became a Christian, but converted back to Zoroastrianism and settled in the industrially wealthy Parsi community of Mumbai. He is the chairman and majority owner of Bombay Dyeing, chairman of the Wadia group, and one of the savviest businessmen of India. The Economic Times described Nusli Wadia as “the epitome of South Mumbai’s old money and genteel respectability”. He has two sons Ness and Jeh.

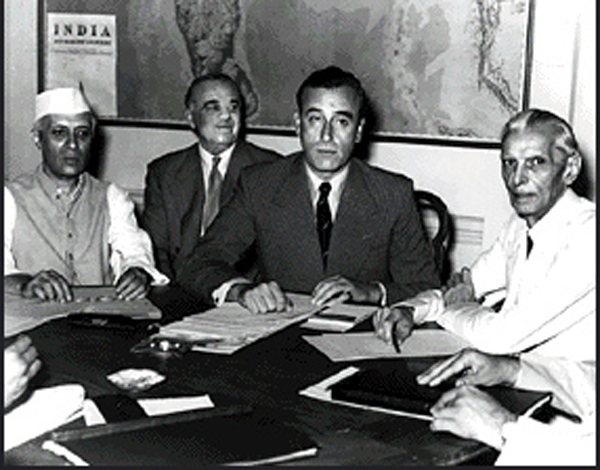

IMAGE: STILL FROM THE MOVIE “MR. JINNAH: THE MAKING OF PAKISTAN” BY AKBAR S AHMED

Dina is 99-years-old and lives in New York with her daughter. Dina’s daughter-in-law, Maureen said to Mumbaiwala about her,

“I think she’s a true New Yorker and she’s doing very well. She knows when the Bloomingdale sales are on, and she’ll tell you when to go down to Saks. We all make it a point to go and see her at least once every two months. When the weather is good in summer, we spend at least a couple of months with her. Nusli visits her very frequently.”

Dina fought for her inheritance, the Jinnah House in Mumbai but she never fought for a place in history. Pakistan, her sibling, does not recognise her.

This post originally appeared on India Currents here.

from The Express Tribune Blog http://blogs.tribune.com.pk/story/30582/nehru-and-jinnah-had-the-same-problem-their-daughters-loved-men-they-did-not-approve-of/

No comments:

Post a Comment